It’s cold and flu season, and we recently had to take our son to the doctor. They tested him for strep throat, and we had the results back in a few hours.

This type of speed is normal in most parts of the economy. In medicine, Congress passed a law in 2016 that prevents doctors and hospitals from “blocking” patients and parents the right to see new test results whenever they’re ready.

But what about education, where parents routinely wait months to see their child’s test scores, if they see them at all? Millions of kids sit for state exams in the Spring each year, but parents are often the last to see the results. This is unacceptable, and the U.S. Department of Education could author a similar rule to give parents quicker access to their child’s test scores.

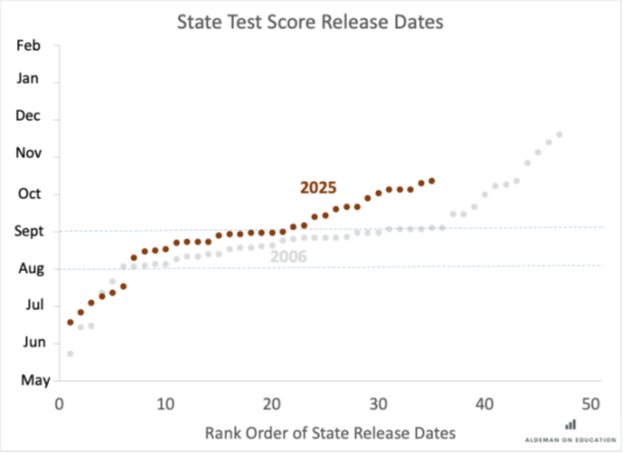

I’ve been tracking the timing of state test score releases off and on for almost two decades now. Back in 2006, when I first helped collect the data as a research assistant for William and Mary Professor Paul Manna, we found that most states were pretty slow, with just five states releasing their results before the end of July, and 16 states holding them until September 1st or later.

In the years since, states have dropped their old paper-and-pencil Scantron tests in favor of online versions. The tests are scored digitally and instantly. And yet, parents have to wait.

How long? In 2025, six states released their results by the end of July. That is, the fastest states today are on par with the fastest states from 2006. But the rest are worse. This year, only 20 states and the District of Columbia released their results before September 1st. Worse, 16 states had still not released their results when I looked in mid-October.

In other words, states have gone from paper-and-pencil tests to computers and somehow gotten slower.

Of course, I’m only able to count what’s publicly available. And it is true that some states release preliminary results privately to parents and educators. I can speak to that myself. As a parent in Fairfax, Virginia, I saw my children’s scores within days of them taking their tests last Spring even though the state didn’t release its official scores until the end of August.

Of course, I’m only able to count what’s publicly available. And it is true that some states release preliminary results privately to parents and educators. I can speak to that myself. As a parent in Fairfax, Virginia, I saw my children’s scores within days of them taking their tests last Spring even though the state didn’t release its official scores until the end of August.

This is as it should be. Parents should see their kids’ scores before the public sees the aggregate totals. Unfortunately, some places are doing the opposite. In Washington, D.C., for example, the city announced the overall results to much fanfare back in August. But, while policymakers were touting some gains, parents were kept waiting for their own child’s results. This is backwards—parents should be first in line, not last—and it’s where the U.S. Department of Education needs to step in.

Current federal law requires states to provide results to parents, teachers and school leaders “as soon as is practicable after the assessment is given,” but the law didn’t define what it meant by “as soon as practicable.” The feds should clarify this rule to require states to send preliminary results to parents and educators within, say, four weeks of the test’s administration.

Now, some education bureaucrats will push back on such a requirement, just like the medical industry pushed back in their sector. They’ll cite technical issues, or argue that results should only come directly from professionals.

The technical argument is entirely bogus. A four-week window for preliminary results falls well in line with the standards in the private sector. Besides, some states are already meeting the four-week goal, suggesting that these concerns are really more about power and control than feasibility.

The professionalism argument is a harder one to casually dismiss. On one hand, parents trust their kids’ teachers more than the state, but there’s also good evidence that parents think their child is doing better than they really are. In one study, 90% of parents thought their child was performing at grade level when only 30% actually were.

Speeding up the delivery of state test results can help close that gap. Educators sometimes struggle to deliver hard news to parents that their son or daughter is not on track academically. Maybe the child is behind in math but behaves well, or the teacher is focused on signs of progress. The state test is meant to be a counter-balance in those conversations and alert parents when their child is behind where they should be for their age.

Congress clearly intended for those messages to reach parents quickly, but in far too many places that’s not happening today. If the feds stepped in on the side of parents, a quick return of test results could be the standard operating practice across the country.