The Gender Gap in Math Starts Early

Gender gaps in math start have been growing in recent years. A recent report from NWEA found that, from 2021 to 2024, boys have steadily pulled away from girls in both math and science. Importantly, this story is not about the averages but about the highest-performing boys pulling away from the highest-performing girls.

A giant study out of France allows us to unpack the sources of these gaps. While the study looks at a different context than ours, it’s notable for the size and scale of its sample. Notably, every year since 2018 all French children have been tested in language and math tests at the beginning of 1st grade, after four months of school, and again 12 months later at the start of 2nd grade. After following four consecutive cohorts, a research team led by Pauline Martinot had a sample size of 2.6 million children.

Martinot’s team revealed two important findings. One, the did boy-girl math gaps develop much earlier than many people might have expected. And two, there was something about the school experience itself that may have contributed to accelerating the trajectory for boys at the expense of girls.

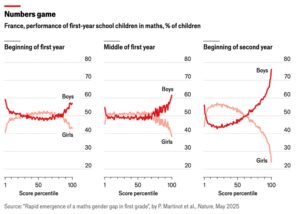

The Economist took Martinot’s results and produced the striking graphs below. At the left is the distribution of math performance of 1st graders. Upon starting school, boys (in dark red) were slightly more likely to land at either end of the performance distribution, either very low or very high, while girls (the salmon color) were more likely to land in the middle. This “males at the tails” trend has been documented before. And on average, girls actually had a very slight advantage over boys when they started school.

But now look at what happens over time. Just four months later, in the middle of the first year, boys are shifting toward the upper end of the performance distribution. And, 12 months after starting school, the graph has turned even more extreme, with boys now earning the large majority of spots at the upper performance levels. Remember, this is effectively the start of 2nd grade!

Martinot and team found that these math gender gaps developed across every region of France, in all types of schools, among students of all different demographics, and in all four cohorts. Notably, the gender gap grew more slowly in the spring and summer of 2020, when French schools were closed for COVID, but has since resumed. In other words, something about the school context may be driving gender math gaps, at least in France.

What can be done about these gender gaps? The French study in particular suggests a need for early monitoring and intervention. As I noted in a recent piece, early math scores are highly predictive of later-life outcomes such as taking advanced courses or pursuing careers in STEM fields. The longer schools wait to remediate these types of math gaps, the harder it will become to get kids back on track.